Research into human fossils dating back to approximately two million years ago reveals that the hearing pattern resembles chimpanzees, but with some slight differences in the direction of humans.

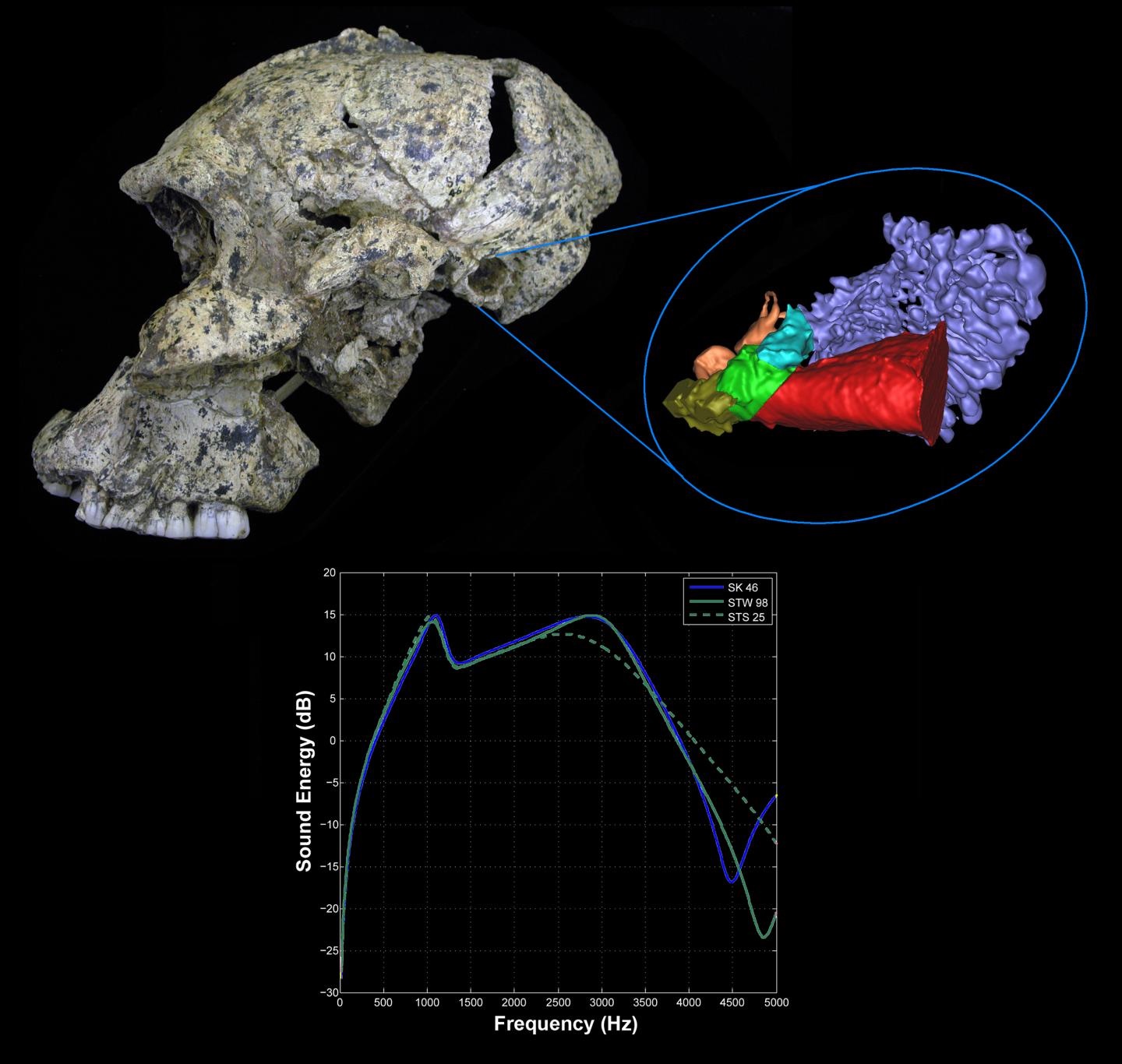

Rolf Quam, assistant professor of anthropology at Binghamton University, led an international research team in reconstructing an aspect of sensory perception in several fossil hominin individuals from the sites of Sterkfontein and Swartkrans in South Africa. The study relied on the use of CT scans and virtual computer reconstructions to study the internal anatomy of the ear. The results suggest that the early hominin species Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus, both of which lived around 2 million years ago, had hearing abilities similar to a chimpanzee, but with some slight differences in the direction of humans.

Humans are distinct from most other primates, including chimpanzees, in having better hearing across a wider range of frequencies, generally between 1.0-6.0 kHz. Within this same frequency range, which encompasses many of the sounds emitted during spoken language, chimpanzees and most other primates lose sensitivity compared to humans.

“We know that the hearing patterns, or audiograms, in chimpanzees and humans are distinct because their hearing abilities have been measured in the laboratory in living subjects,” said Quam. “So we were interested in finding out when this human-like hearing pattern first emerged during our evolutionary history.”

CREDIT : Rolf Quam

Previously, Quam and colleagues studied the hearing abilities in several fossil hominin individuals from the site of the Sima de los Huesos (Pit of the Bones) in northern Spain. These fossils are about 430,000 years old and are considered to represent ancestors of the later Neandertals. The hearing abilities in the Sima hominins were nearly identical to living humans. In contrast, the much earlier South African specimens had a hearing pattern that was much more similar to a chimpanzee.

In the South African fossils, the region of maximum hearing sensitivity was shifted towards slightly higher frequencies compared with chimpanzees, and the early hominins showed better hearing than either chimpanzees or humans from about 1.0-3.0 kHz. It turns out that this auditory pattern may have been particularly favorable for living on the savanna. In more open environments, sound waves don’t travel as far as in the rainforest canopy, so short range communication is favored on the savanna.

“We know these species regularly occupied the savanna since their diet included up to 50 percent of resources found in open environments” said Quam. The researchers argue that this combination of auditory features may have favored short-range communication in open environments.

That sounds a lot like language. Does this mean these early hominins had language? “No,” said Quam. “We’re not arguing that. They certainly could communicate vocally. All primates do, but we’re not saying they had fully developed human language, which implies a symbolic content.”

The emergence of language is one of the most hotly debated questions in paleoanthropology, the branch of anthropology that studies human origins, since the capacity for spoken language is often held to be a defining human feature. There is a general consensus among anthropologists that the small brain size and ape-like cranial anatomy and vocal tract in these early hominins indicates they likely did not have the capacity for language.

“We feel our research line does have considerable potential to provide new insights into when the human hearing pattern emerged and, by extension, when we developed language,” said Quam.

Ignacio Martinez, a collaborator on the study, said, “We’re pretty confident about our results and our interpretation. In particular, it’s very gratifying when several independent lines of evidence converge on a consistent interpretation.”

How do these results compare with the discovery of a new hominin species, Homo naledi, announced just two weeks ago from a different site in South Africa?

“It would be really interesting to study the hearing pattern in this new species,” said Quam. “Stay tuned.”

The study was published on Sept. 25 in the journal Science Advances.