A French-Kenyan research team has just described a new fossil ancestor of today’s hippo family. This discovery bridges a gap in the fossil record separating these animals from their closest modern-day cousins, the cetaceans.

It also shows that some 35 million years ago, the ancestors of hippos were among the first large mammals to colonize the African continent, long before those of any of the large carnivores, giraffes or bovines.

The ancestry of hippopotamuses is somewhat of an enigma. For a long time, paleontologists thought these semi-aquatic animals, with their unusual morphology (canines and incisors with continual growth, primitive skull and trifoliate tooth-wear pattern), to be related to the Suidae family, which includes pigs and peccaries. But in the 1990s and 2000s, DNA comparisons showed that the hippo’s closest living relatives were the cetaceans (whales, dolphins, etc.), which disagreed with most paleontological interpretations. Moreover, the lack of fossils significantly hindered attempts to uncover the truth about hippo evolution.

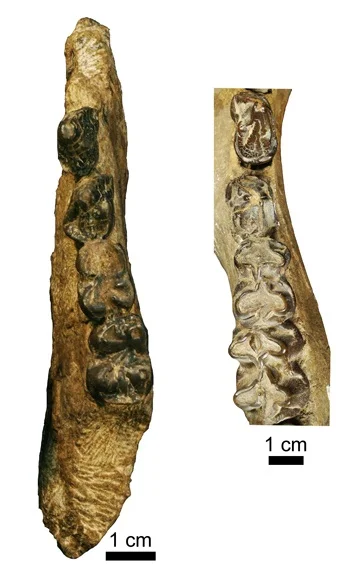

New paleontological work by a group of French and Kenyan researchers has now revealed that hippos are not related to suoids but instead descend from another, now extinct, group. The new fossils studied have made it possible to build the first evolutionary scenario that is compatible with both genetic and paleontological data. By analyzing a half-jaw and several teeth discovered at Lokone (in the Lake Turkana basin, Kenya), the French-Kenyan team described a new fossil species (belonging to a new genus (2)), dating back to about 28 million years. They named it Epirigenys lokonensis, from the word “Epiri” which means hippo in the Turkana language and the site of discovery, Lokone.

By comparing the characteristics of fossil teeth with those of ruminants, suoids, hippos and fossil anthracotheres (an extinct family of ungulates), the scientists reconstructed the relationships between these groups. The results show that Epirigenys forms a kind of evolutionary transition between the oldest known hippo in the fossil record (about 20 million years ago) and an anthracothere lineage. This position in the tree of life is compatible with the genetic data, confirming that the cetaceans are the hippos’ closest living cousins.

This kind of discovery may one day enable scientists to draw a picture of the common ancestor of cetaceans and hippos. Indeed, analysis of Epirigenys (28 million years old) has linked today’s hippos to a lineage of anthracotheres, the oldest of which date back about 40 million years. However, until now, the earliest known ancestor of the hippos was about 20 million years old, while the first fossils of cetaceans are 53 million years old. The time gap between today’s hippos and the oldest cetaceans is thereby filled by nearly 75% according to the present scenario.

Furthermore, this discovery shows the whole history of the African fauna in a new light. Africa was an isolated continent from about 110 to 18 million years ago. Most of the iconic African fauna (lions, leopards, rhinos, buffaloes, giraffes, zebras, etc.) are relatively recent arrivals on the continent (they have been there less than 20 million years). Until now, the same was believed to be true of hippos, but the discovery of Epirigenys demonstrates that their anthracothere ancestors migrated from Asia to Africa some 35 million years ago.

CNRS (Délégation Paris Michel-Ange)