An interdisciplinary consortium of researchers from Oslo University and the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, for the first time, demonstrate that climate-driven plague outbreaks in Asia were repeatedly transmitted over several centuries into southern European harbors.

This finding contrasts the general believe that the second plague pandemic “Black Death” was a singular introduction of Yersinia pestis from Asia to Europe in 1347 AD. Their results are published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States.

To date, scientists were mainly seeking to discover long-term wildlife reservoirs of Yersinia pestis in Europe and aiming to link those with possible climatic triggers that most likely contributed to the “Black Death” that struck the Old World in mid-14th century. Scholars at CEES and WSL, however, found new evidence that challenged the prevailing view of a singular introduction of the bacterium from central Asian plague foci into the Mediterranean harbors of medieval Europe.

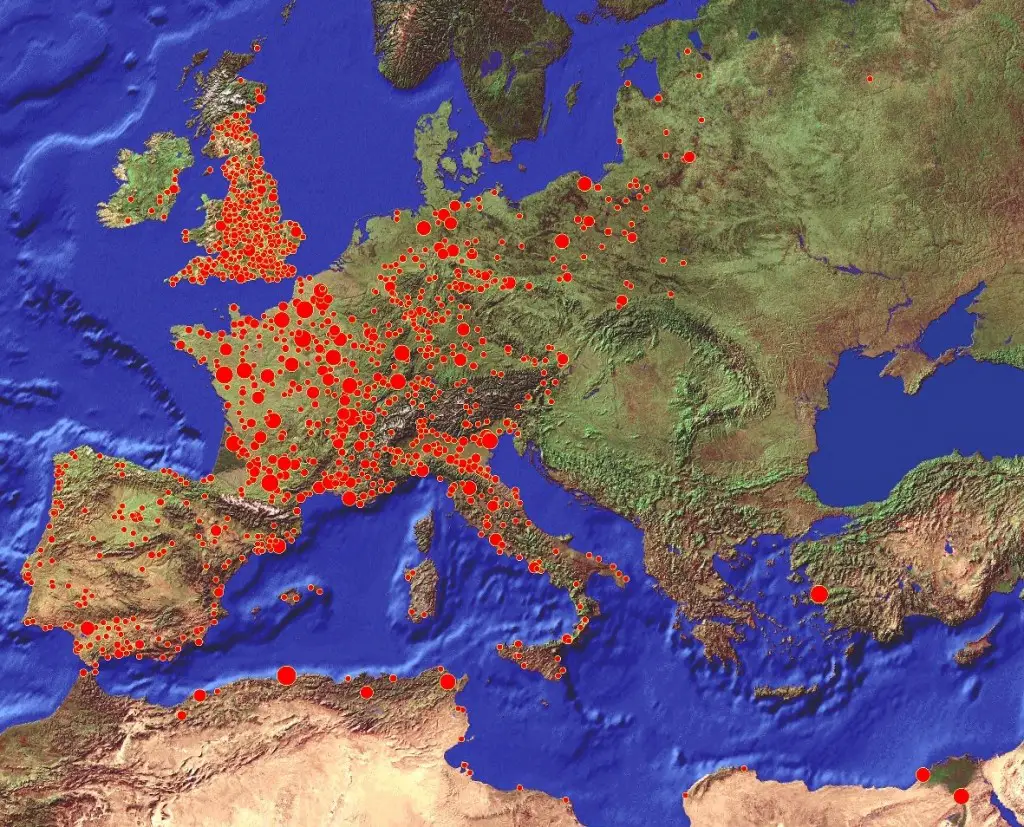

Rather than a rare one-time event that decimated the European population by estimated 40-60% within several years after 1347 AD, the team shows that wildlife rodent population dynamics in central Asia played an important role for the entire second plague pandemic in the Old World. This episode lasted for more than four centuries and substantially impacted the continent’s socio-economic development, culture, art, religion and politics. By comparing a most comprehensive digital inventory of historical plague outbreaks (7711 cases) against 15 annually resolved and absolutely dated tree ring-based climate reconstructions, it became obvious that east-west travelling waves of Asian plague epidemics repeatedly reached Europe.

The team searched for climate fluctuations in high-resolution palaeoclimatic records that are associated with current-day plague outbreaks in major host species (such as the great gerbil Rhombomys opimus), and found such fluctuations to statistically relate with reintroductions of plague into medieval Europe. The new evidence suggests repeated climate-driven re-introductions of the bacterium Yersinia pestis via the Silk Road system into European harbors from wildlife rodent reservoirs in Asian plague foci, with a delay of 10-15 years after pluvial periods that affected large parts of central Asia.

In joining forces, Swiss and Norwegian scientists have expanded the role of Asian wildlife plague reservoirs from a single initiator of the devastating pandemic, to a continuous, climate-driven source of plague in the Old World. Moreover, their results challenge the long-standing, but poorly substantiated view that Yersinia pestis must have had a permanent wildlife reservoir in Europe, such as the urban black rat. Instead, new strains of the disease may have been frequently imported from Asia.

Nevertheless, an ultimate confirmation of this hypothesis depends on the availability of appropriate genetic material of ancient plague victims not only from different periods throughout time but also from different parts of Eurasia. The advent of aDNA techniques and international research collaboration across disciplinary boundaries will most likely be able to shed new light on this fascinating topic at the interface of human history and environmental variability.

Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL