Archaeologists have discovered a network of submerged stone structures off the coast of Sein Island in Brittany, France.

A new study, published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, documents granite complex structures located at a depth of between seven and nine metres below today’s current sea level.

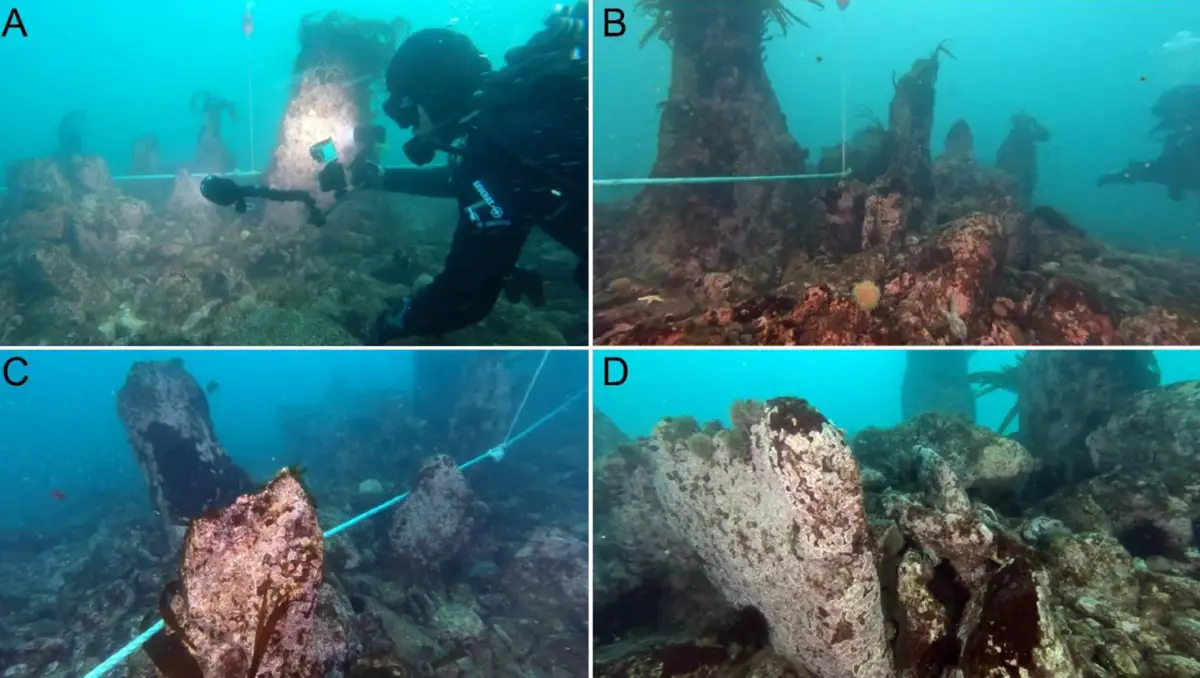

Between 2022 and 2024, a LIDAR survey and numerous diving expeditions confirmed that the structures have a linear alignment and date from approximately 5800–5300 BC during the late Mesolithic period and Neolithic transition.

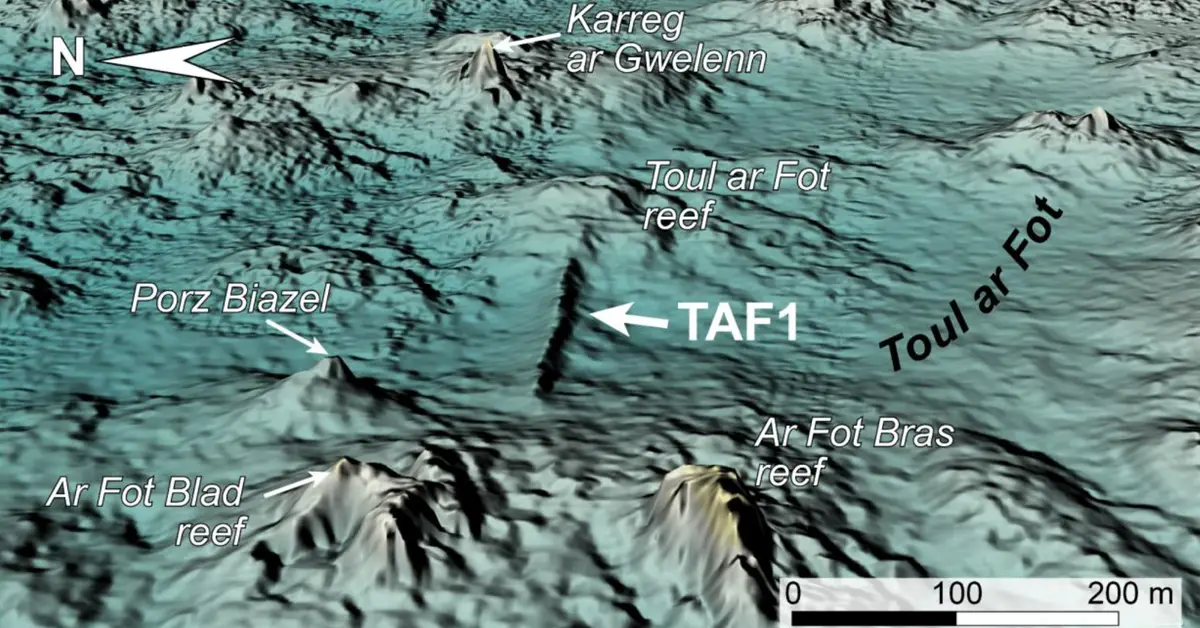

“Four structures (named TAF1, TAF2A, TAF2B, and TAF3) were identified based on the analysis of the Digital Elevation Models in the Toul ar Fot (TAF) sector. They are located 1.9 kilometres west of Sein Island and halfway between the northern and southern edges of the submarine plateau,” said the study authors.

The largest, TAF1 forms a 120-metre-long wall and runs across a submerged valley. The wall is constructed with stacked stone blocks and has more than 60 vertical monoliths and slabs erected on the summits at heights of up to 1.7 metres.

TAF2A has a similar architecture to that of TAF1 and consists of an accumulation of blocks reinforced by monoliths emerging a maximum of 1 metre from the summit.

In 2024, divers also identified four additional structures: YAG1, YAG2, YAG3B, and YAG3C – each comprising linear stone walls built from decimetre-sized blocks positioned to close off small depressions or valleys. Of note is YAG3C, a 50-metre-long wall built from small monoliths spaced roughly a metre apart, sometimes arranged in two or three parallel lines.

In Brittany, local folklore has long spoken of a sunken city said to lie beneath the western reaches of the Bay of Douarnenez, just 10 kilometres east of Sein Island.

The study authors suggest that the presence of human-made stone structures now raises questions about the potential prehistoric origin of the legend. “It is likely that the abandonment of a territory developed by a highly structured society has become deeply rooted in people’s memories.”

While the submerged structures off Sein Island are all undoubtedly related, experts suggest that smallest structures could possibly serve as fish weirs. “The largest structures, much larger than currently known dimensions for fish weirs, may also have had a protective role. The size and technical nature of the largest structures have no known equivalent in France for this period,” concluded the authors.

Sources : International Journal of Nautical Archaeology