The Jade burial suits are hand-crafted jade suits from the Han Dynasty of China, used for the ceremonial burials of China’s elite and members of the ruling class.

The Chinese developed a fascination with Jade as early as 6000 BC during the Neolithic period, producing ritual and ornamental tools or weapons as symbols of political power and religious authority.

One of the first known centres of Jade manufacturing occurred in the Yangtze River Delta of China by the Liangzhu culture (3300–2300 BC), sourcing nephrite jade for utilitarian and ceremonial jade items from the now depleted deposits in the Ningshao area.

Jade was also heavily sourced in an area of the Liaoning province in Inner Mongolia by the Hongshan culture (4700–2200 BC), producing jade objects in the shapes of pig dragons or zhūlóng and embryo dragons.

With the emergence of the Han Dynasty (the second imperial dynasty of China) from 202 BC, jade objects were increasingly embellished with animal and other decorative motifs, whilst low relief work in objects such as the belt-hooks became part of elite costume.

Because of its hardness, durability, and subtle translucent colours, jade became associated with Chinese conceptions of the soul, protective qualities, and immortality in the ‘essence’ of stone (yu zhi, shi zhi jing ye).

The association with jade’s longevity is apparent from text by the Chinese historian Sima Qian (145 – 86 BC) about Emperor Wu of Han (157 BC –87 BC), who was described as having a jade cup inscribed with the words “Long Life to the Lord of Men”, and indulged himself with an elixir of jade powder mixed with sweet dew.

The Han thought that each person had a two-part soul: the spirit-soul (hun 魂) which journeyed to the afterlife paradise of immortals (xian), and the body-soul (po 魄) which remained in its grave or tomb on earth and was only reunited with the spirit-soul through a ritual ceremony. The early Han rulers came to believe that jade would preserve the physical body and the souls attached to it in death, with various burials being found with large and small jade bi discs placed around the deceased.

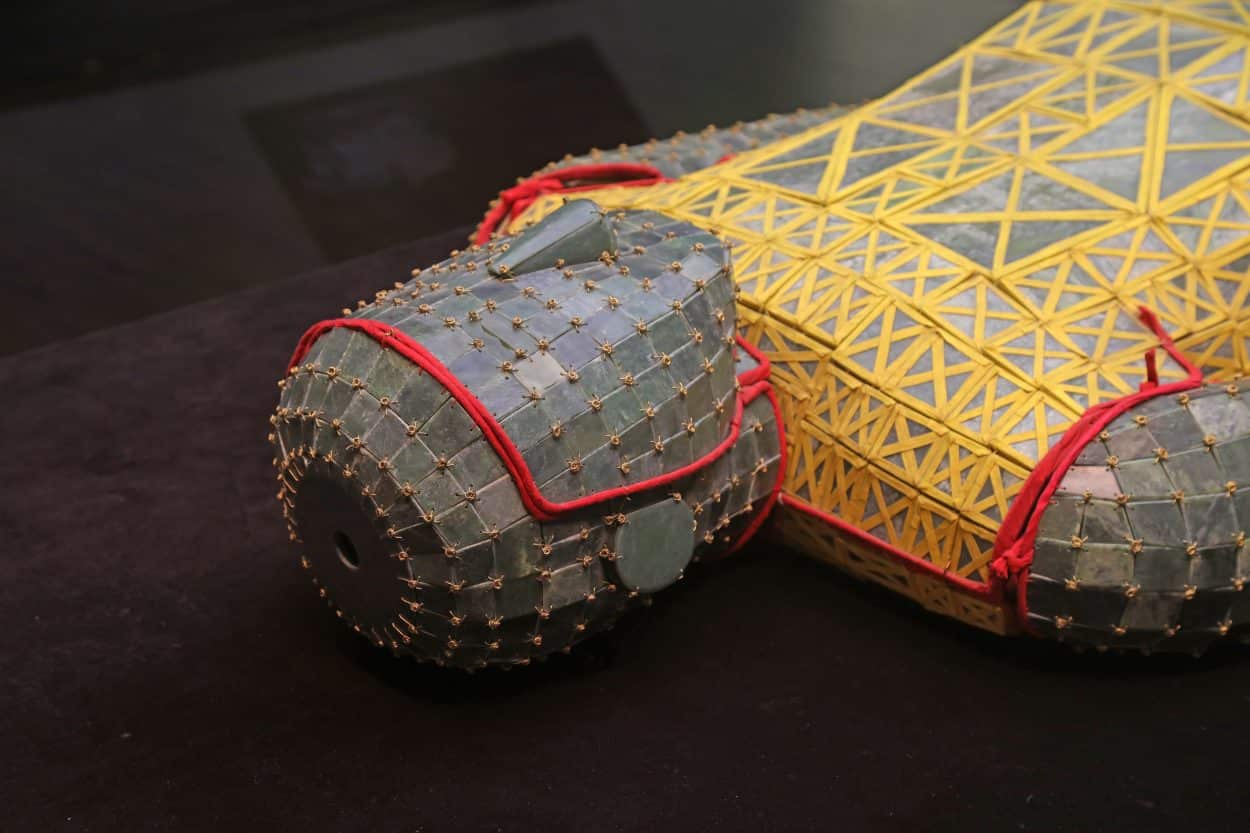

This developed into the practice of being buried in ornate jade burial suits, completely encasing the deceased in thousands of pieces of cut and polished jade sewn together with thread, believing that the suit ensured the body would remain immortal. It is estimated that it would require hundreds of craftsmen more than 10 years to polish the jade plates required for a single suit, emphasising the power and wealth of the deceased.

According to the Hòu Hànshū (Book of the Later Han), the type of thread used was dependent on status. An emperor’s jade suit was threaded with gold, whilst lessor royals and high-ranked nobility with silver, sons and daughters of the lessor with copper, and lowly ranked aristocrats with silk.

It is believed that the practice ceased during the reign of the first emperor of the state of Wei in the Three Kingdoms period (AD 220-280), in fear of tomb robbers who would burn the suits in order to retrieve the gold or silver thread.

The mention of jade suit burials in historical text was long suspected as merely legend, until the discovery of two complete jade suits in the tombs of Prince Liu Sheng and his wife Princess Dou Wan in Mancheng, Hebei in 1968, with a total of 20 known jade burial suits being discovered in China to date.

Header Image Credit : Maksim Gulyachik