Insects and terrestrial arthropods have inhabited the Earth since before the time of the dinosaurs, growing much larger to their contemporary equivalents during the Carboniferous period, due in part to a surplus of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere.

This growth was supported by higher planetary temperatures that increased metabolism, with some theories also suggesting that the evolutionary growth spur was to avoid oxygen poisoning.

It is also possible that both groups grew to compete in an evolutionary arms race to take down large prey or to ward off predation, as the absence of key predators such as birds in the food chain wouldn’t evolve until 150 million years ago.

Fossil records suggest that insects emerged around 407 to 396 million years ago, with the earliest example being Devonian Rhyniognatha hirsti during the Early Devonian aged Rhynie chert around 400 million years ago.

The first fossil arthropods appeared in the Cambrian Period between 541.0 million to 485.4 million years ago, although the first terrestrial colonisers came ashore during the Early Silurian 443.8 million years ago.

During the Carboniferous period, which lasted from about 359 to 299 million years ago, vast lowland swamp forests caused an increase in atmospheric oxygen levels that supported a multitude of giant creatures, one of the most common being giant dragonflies known as griffinflies from the Meganeuridae family.

The largest from the genus was Meganeura Monyi, a dragonfly that had a wingspan ranging from 65 cm to 70 cm. Meganeura Monyi was a predatory insect evolving spines on the tibia and tarsi sections of the legs to capture smaller prey.

Another flying insect was Mazothairos from the Palaeodictyoptera group of paleopterous insects. Mazothairos is estimated to have had a wingspan of about 56 centimetres and evolved a beak-like mouthpart with elongated sharp stylets for piercing plant tissue.

Land based insects and arthropods also grew to immense sizes, where genus of millipedes, scorpions and proto-cockroaches amongst others, competed on the forest floor.

One of the largest of these was Arthropleura Armata, a genus of millipede that inhabited coal forests and could grow up to 2.5 metres in length. Arthropleura is the largest known land invertebrate to ever exist, but is believed to have been an herbivore, living on a diet of fruits, sporophylls and seeds.

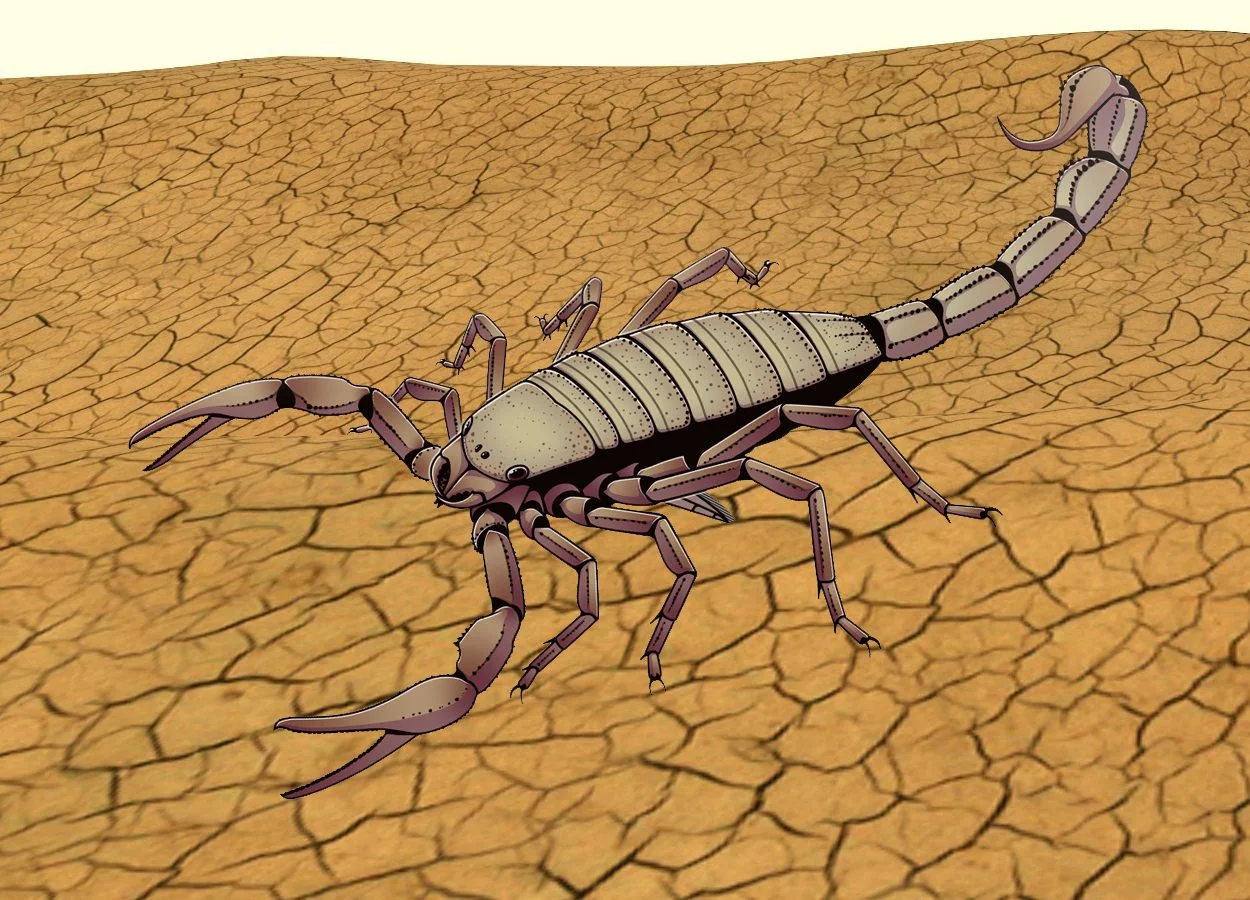

Another giant floor dweller is Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis, an early predatory arachnid of the order Scorpiones which hunted the forest floor for smaller arthropods. Most complete specimens were 13–280 mm in length, while a large, fragmentary specimen is estimated to have been 70 cm long when alive.

Around 305 million years ago, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels began decreasing significantly, causing the average global temperature to drop from 20 °C to around 12 °C. This resulted in forests receding to isolated patches, eventually leading to the minor extinction of most of the larger giants of the Carboniferous.